To a chef and a medical researcher, the thought of immersing a pig’s tissue in a warm water bath doesn’t seem all that strange.

To a chef, it’s a way of preparing meat using the sous vide method, where cooking is done over a long period of time in a steady warm water bath — this still-novel method brings out complex flavours.

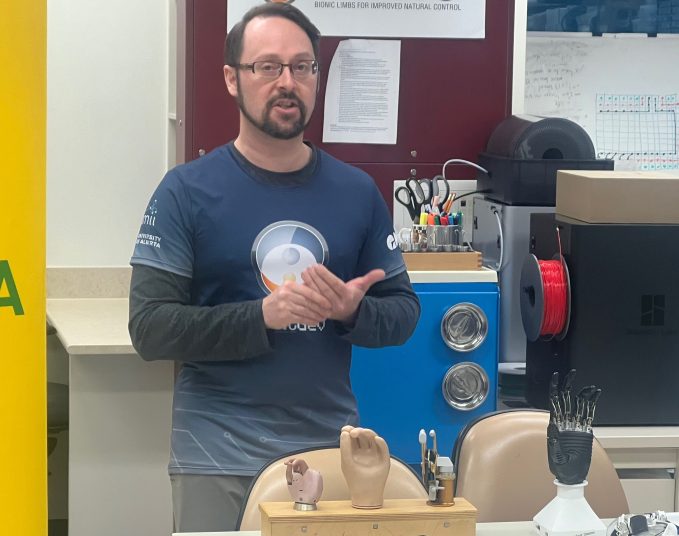

For a researcher like the University of Alberta’s Matthew Douma, pig’s tissue is about as close as you can get in the animal kingdom to human tissue. And that’s what he used to test the prototype of his new rewarming device, which he hopes will help reduce the number of frostbite-related amputations we’re seeing in Edmonton.

This past year, Edmonton hospitals performed 110 frostbite amputations. Douma is an Edify Top 40 Under 40 alumnus who’s an adjunct professor of critical care at the U of A, a clinical care researcher and has years of real-world experience in emergency rooms as a registered nurse. These numbers made him ask himself a lot of questions.

“When I saw the frostbite numbers, I felt a wave of karma and dread,” says Douma. “I worked for 15 years in emergency departments, and I saw that we were not providing the therapies that probably we should have been.”

He founded Miteh Health Solutions (“Miteh” is Cree for “heart,” and Douma feels his work is an act of reconciliation). It’s a social enterprise. And Douma’s goal was to create a device that would allow for patients’ extremities to be “rewarmed” just minutes after they came through an emergency ward’s doors. He says that treatments should be started within 10 minutes of a patient’s arrival, as each second of delay is critical. Frostbite means that ice crystals have formed, the blood has stopped flowing, and the tissue is dying.

His solution was a simple one. Douma was fully aware that labs are equipped with machinery that can keep water held at precise temperatures for long periods of time. This is important for experiments and growing cultures. That technology then made its way into kitchens around the world as a sous vide cooker.

“This is very much like a sous vide,” he says. It has an automatic shutoff that ensures the water can’t be heated past 50 degrees celsius.

He first tested it on pig tissue, then asked friends and family to dip their hands and feet into it. With the early onset of cold and snow in 2024, he accelerated the process to get one unit operational and into an emergency ward. The device is now in front of Alberta Health Services for approval. A big part of that is to see how quickly the device can be sterilized and prepared, to ensure it can be used again and again by different patients.

“It’s a chain of care that a winter city like Edmonton desperately needs,” he says.

Douma says that Edmonton’s rate of frostbite amputations is the highest in the world — of anywhere that keeps records of that sort of stuff. He allows that it’s possible that numbers could be higher in a place like Russia. But Edmonton is a western, modern city that shouldn’t have numbers this high.

Many of the amputees are unhoused. And many are men in their mid-40s.

And what should you do if you’re out in the cold? It’s normal for us to start feeling pain in our fingers and toes when we’re out in frigid temperatures. But the big issue is if it stops hurting.

“If the pain goes away, it’s a real red flag,” Douma says.

And, if you see fluffing of tissue or blisters, it’s time to get urgent care.

Savvy AF. Blunt AF. Edmonton AF.