Walk through Sea Change brewing’s new space, and you will see rows of large silver vats. There are flats filled with beer cans.

But, it’s clearly a work in progress. In the front of the building, a bar has been roughed in. Right now, it’s a collection of wood beams and dreams. In the production area, near the beer vats, there’s a copper still, glass door open.

Sea Change is a local brewery that’s been around for five years, and its name is well-known in the Edmonton area. It was born with the brewery and tap room near Argyll Road, and has grown to include a taproom in Beaumont and the new facility just off 99th Street, known as Happy Beer Street. But, make no mistake, it’s still a small business.

And the owners want to expand. Part of the plan is for Sea Change to expand into spirit production. Under the Shiddy’s brand, it’s already making canned ready-to-drink (RTD) “sparkling vodka” beverages. When the bar opens, it won’t just pour Sea Change beer, but clear spirits and, down the road, whiskey.

They’re part of a revolution in the provincial brewing and distilling industry. In 2013, the province repealed a rule that didn’t allow anyone to make and sell alcoholic beverages unless they produced 500,000 litres of the stuff a year. As of today, the Alberta Craft Distillers Association (ACDA) has more than 30 members on its web page.

Despite the rapid growth in the number of distilleries, make no mistake — these are anything but get-rich-quick businesses. In fact, there are many, many challenges the industry faces as a whole. The Sea Change group is finding that out.

Safety codes require distilleries to have industrial-level building requirements. That roughed-in bar at the front needs to be separated from the distillery itself with walls that aren’t just fireproof, but blast proof. It’s written in the regulations that distilleries are seen as “high-hazard industrial occupancies.”

And, then there’s the issue of tax. The ACDA is leading a charge for the province to simplify the tax regime.

“In Alberta, producers struggle to expand their operations and achieve province-wide distribution,” says Stavros Karlos, the executive director of the Alberta Craft Distillers Association. “We need to be successful in our home base, first and foremost.

“For us, it’s about creating a level playing field, and a runway for people to achieve growth.”

The Markup

When an Alberta distiller making a beverage of 40 per cent alcohol or higher wants to distribute to this province’s liquor stores through the warehousing and distribution hub, Connect Logistics, a $13.67 markup is applied for every litre. Most bottles are 750 mL, so that’s about $10.25 a bottle. If you wonder why so many locally made gins and vodkas are more than $50 a bottle, the markup is a big part of it.

In 2017, the then-NDP government announced a lower markup rate for producers who sell direct to customers, known as “farm gate.”

“We believe that Alberta’s small liquor manufacturers play an important role in creating jobs and building a diversified economy,” said Joe Ceci, then the minister of finance. “This program will allow manufacturers to hire staff, expand production and reinvest in their businesses. Alberta produces some of the best agricultural products in the world and these manufacturers work hard to turn them into high-quality spirits. We will continue to work with this industry to ensure they can do business in Alberta as easily and successfully as possible.”

That “farm gate” rate was just $2.46 per litre, compared to the $13.67 Connect rate. But it didn’t create the boom that Ceci predicted. That’s because there are other costs associated with taking advantage of the lower rate. It means that distilleries would pay more in shipping. And, for many, the costs to try to distribute their products themselves far outweigh the benefits.

“Alberta is quite a spread-out province,” says Karlos. “ If you’re a distillery in Fort McMurray, shipping down to Calgary makes no sense. It becomes completely uneconomical. And most retailers prefer to do their shopping through Connect, it’s central and it’s easy to use. It’s one fixed shipping rate across the province.”

But this is where it gets confusing. Beer makers, if they’re making products with less than eight per cent alcohol, face only a $1.81-per-litre markup when going through Connect, and 32 cents per litre via “farm gate.” Nobody in the distilling community — or the beverage-making community as a whole — wants to see brewers’ rates go up.

And where those distilleries can get that advantage is through RTDs. Yes, those hard seltzers or pre-mixed canned drinks that are all the rage. And they can inject needed front-end money for distilleries. Let’s face it, RTDs aren’t about the quality of the mix; you drink them for the fruity flavours. They are patio or game-day drinks. And brewers and RTD makers would like to see the rates to sell through Connect harmonized with the “farm gate” rate at 32 cents/litre.

The RTD cans bring cash flow up front — like the Shiddy’s product does for Sea Change.

Sea Change is currently bringing in neutral alcohol for its RTD drinks, because it doesn’t make any economic sense to distill from scratch what’s essentially a mix.

“We want to see harmonization between Connect and the farm-gate rates for RTDs,” says Karlos. “Most distilleries in Alberta, and a significant number of breweries, are producing RTDs. It’s the fastest growing spirit category. In the U.S. RTD sales grew 38 per cent year over year, which is just bananas growth.”

The Subsidies

Liquor is heavily taxed and regulated, no matter where you go in the world. What sets Alberta apart? After all, we have a privatized liquor industry. Canada is a very complicated place when it comes to transportation and sales of liquor. Each province controls its liquor industry, so the country is broken down into fiefdoms. It is expensive, and paperwork-heavy, for a small distiller or brewer to sell in another province.

“The problem is, all the provinces hate each other,” says Pete Nguyen, a Sea Change partner. “It would be easier for us to sell our stuff in Japan than in B.C. or Ontario.”

Going over all the esoteric provincial barriers to trade in liquor would be a book unto itself. No one in Alberta’s distilling business is expecting B.C. or Ontario or Quebec to change their regulations. No one is expecting it to get any cheaper to export drinks to the United States. What they want, though, is the ability to get a break at home, so they can build their businesses and Alberta. And, once the business is profitable in Alberta, they can then make their plans to take their stuff to new markets.

“The United States has given a home-field advantage to their distilling industry with a reduction of the tax rate,” says Karlos. “So, they’re able to succeed at home first before moving into the export market. We just don’t have a home-field advantage.”

In Ontario, small distillers can apply for a subsidy of up to $4.42 per litre, for the first 200,000 litres produced in a year. That’s an advantage that Alberta distillers don’t have. And Karlos said the legality of such a direct subsidy is not challenged by anyone outside of Ontario, because that province’s closed market is so coveted. Sue Ontario and risk being punished by not being allowed to sell in Ontario — that’s the fear.

Alberta used to give grants to small brewers, but was successfully sued by Saskatchewan’s Great Western Brewing Co. and Ontario’s Steam Whistle (for more than $2 million). The difference? Because Alberta has an open liquor market, while Ontario has a closed one, out-of-province producers aren’t afraid of retribution.

That’s why the distillers see the need for a tax break, not a subsidy.

Whiskey

“Alberta should be the number-one whiskey producing province in the country,” Karlos says. With access to some of the best grain the world has to offer, our distillers should one day be famed around the world for the best whiskey in the world.

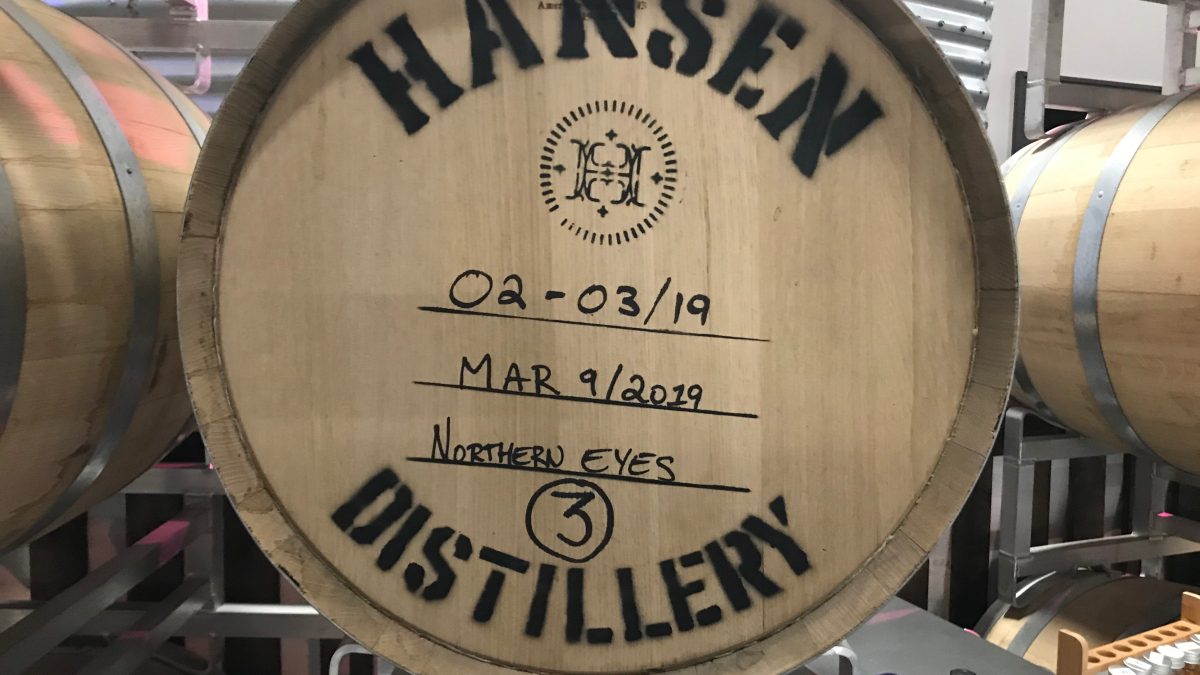

Whiskey also has the potential to be far more profitable than gin or vodka, but, because whiskey has to be aged a minimum of three years, and older whiskies can be sold for more than younger varieties, a distillery has to invest in not only production, but barrels and storage.

And this gets back to the point about distillers needing to generate more revenue up front, so they can invest more confidently in the future.

“Most of the distillers in this province are interested in entering the whiskey market, so a lot of the clear spirit operations are a way to generate cash flow,” says Karlos. “In the United States, that’s typically what the transition is for distilleries that aren’t well capitalized in the front end.

“Alberta has over 100 years of history in whiskey production. If we’re looking for opportunities to grow this industry, and grow it beyond provincial borders, how do we get to that point? What products have that export potential? For Alberta, it’s 100 per cent whiskey. But whiskey is intensely capital-heavy and you’ve got to be patient. That’s the linkage we’re trying to create with government so they can try to better understand our industry.”

The Code

Distilleries are regulated by building and safety codes as heavy industries, with hazardous materials on site. And that means there are limits to how many visitors they can have. A distillery can try to sell directly, or have a tasting room and kitchen, but they’re subject to a lot of code regulations. Many Alberta regulators limit occupancies of tasting rooms at 30 people.

As well, under these heavy industrial uses, distilleries aren’t allowed to have “public” occupancies. So, no tours, visits or big events. Go to Scotland, and distillery tours are well, big tourist draws. Legally, we can’t do the same here.

“Those codes were written when the only distilleries that existed in this country were massive production facilities,” says Karlos. “These were totally different scales of production.

“There are at least three projects in this province that I know of that are at a standstill. These aren’t hillbilly guys. These are multi-million dollar projects that can’t get their approvals because the inspectors have hardened their stances on them. There’s a balancing point between risk and infeasibility.”

In 2021, after a change in New York rules, the Great Jones Distilling Co. opened in the heart of Manhattan, and it offers tours and interactive experiences. These are the sorts of tools that create a tourist industry around distilling. But it required government to see distilling as something that could be done in public view, in dense urban spaces.

The ACDA has been talking to safety-code regulators, trying to find compromises. For example, if a distillery goes to a professional engineer to find cost-effective ways to operate, and keep visitors safe at the same time, should these be considered?

“What we’re asking for is for us to be able to utilize professional services, like engineering firms, to give us alternative measures in order to satisfy the requirements,” Karlos says. “We’re not asking to be above the law, we’re asking to follow the law with professional help.”

Right now, there’s a roughed-in space at Sea Change’s new facility, waiting to be filled. It’s an example of a burgeoning industry that, despite a boom in the number of distilleries that have opened in Alberta, is still “struggling to get by,” according to Karlos.

“They need to get to the point where they can release a high-value product, like whiskey, or get their operations under control over the course of a number of years.”

Savvy AF. Blunt AF. Edmonton AF.