Rossdale’s river valley view won’t have the same pop of autumn colour this time next year now that Edmonton has green-lit a project that will see more than 550 trees removed from the community.

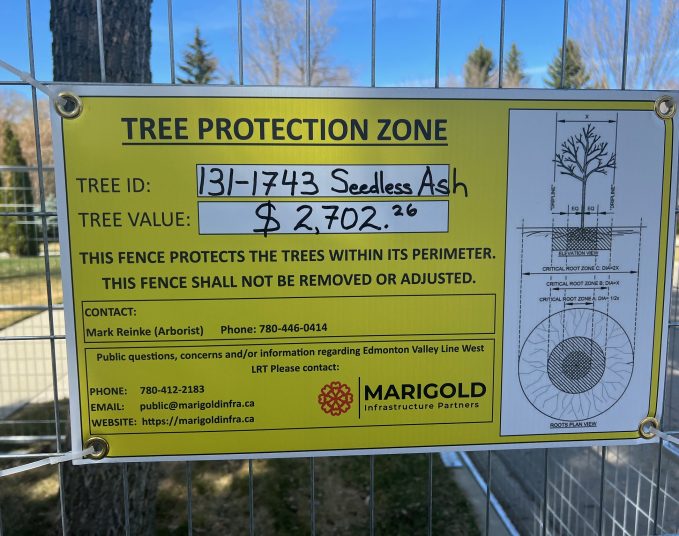

The move is part of EPCOR’s Water Treatment Plants Flood Mitigation Project, which was before the City’s utility committee last week. The approved project will remove trees (and other vegetation) to build “flood barriers” around both the Rossdale and EL Smith water treatment plants to protect them (and the city’s water supply) from flood damage.

Project Manager Yolanda Casciaro said construction of the barriers will start in 2024 and site preparation will begin in the coming months.

Now, no one likes the idea of axing that many trees – especially in the downtown river valley – but before you go chaining yourselves to any tree trunks consider that not going ahead with the project has the potential to be even worse.

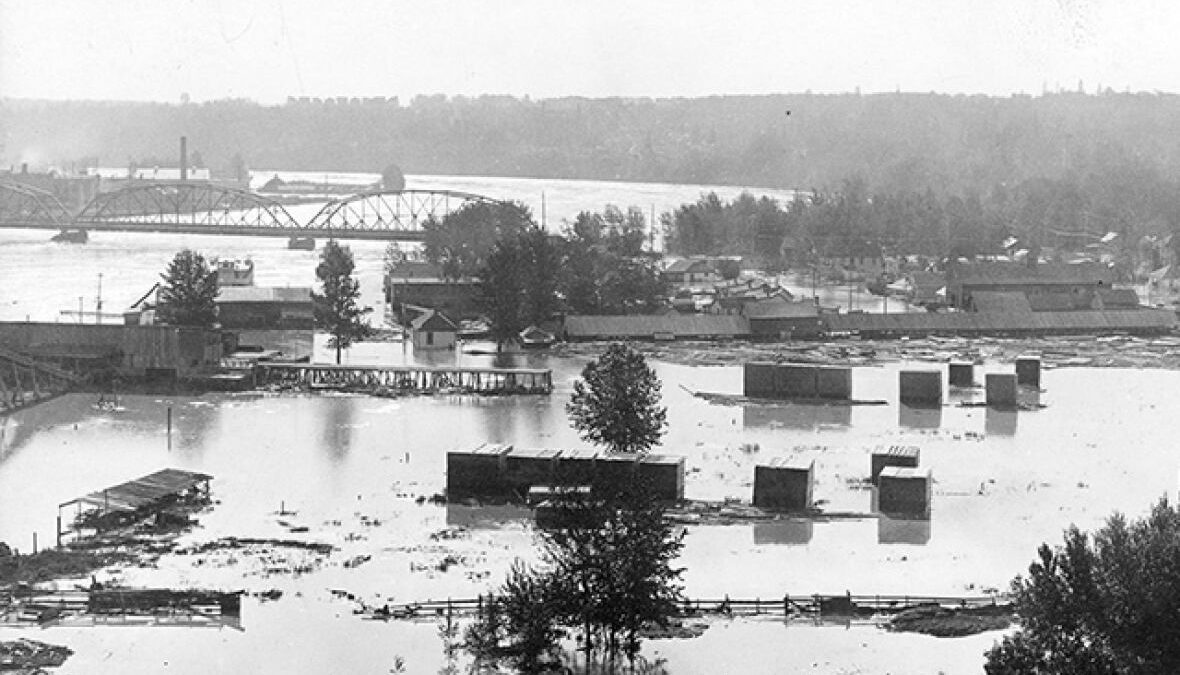

Alberta predicts a high likelihood of flooding in the Rossdale area over the next 30 years. And with severe weather events increasing year after year, EPCOR (and, of course, its insurer FM Global) is worried about the consequences of what might happen if the water-treatment plants were to become swamped.

If the plants were to be knocked offline by floods, the city could be without clean drinking water for up to 10 months, according to EPCOR’s project proposal. That’s a long time to truck in and ration what little water is available, not to mention the cost of repairing the plants and mitigating environmental damage.

But that’s not to say that these projects aren’t without concern – the utility has promised to re-naturalize the area they disturb upon completion but hasn’t come forward with any concrete plan on how that will be done.

Casciaro said EPCOR plans to revitalize an area larger than they remove, including within the water plant fence lines. They were, however, vague about what type of re-naturalization would be implemented and where.

“This is a prairie parkland eco region and there are various stages of parkland that exist,” Casciaro said. “Those stages vary from forested areas to grasslands that are natural to the area. Our vegetation management plan provides the opportunity for us to look at all those stages and where they can be implemented as appropriate.”

Coun. Anne Stevenson, who sits on the City’s utility committee and whose ward Rossdale resides within, says the committee has asked EPCOR to come before council with a finished revitalization plan.

“This will provide us a chance to review the full details of how biodiversity and wildlife connectivity will be supported through this project,” Stevenson said.

The Edmonton River Valley Conservation Coalition (ERVCC) also has concerns, citing environmental impact and lack of discussion around alternative options.

“There are many problems with this project, including the cutting of 557 trees … further degradation of the wildlife corridor and further impact to sacred Indigenous sites,” ERVCC chair Kristine Kowalchuk said.

EPCOR has, according to their proposal documents, consulted with various Indigenous communities regarding the project.

Kowalchuk also noted concern over the location of where the two treatment plants presently sit.

“We would have liked to have seen City Council require EPCOR to explore decentralization of its water treatment and removal of some infrastructure from the river valley,” she said. “This is a lot less costly than losing the drinking water and infrastructure upon which the entire city… depends on if the concrete does not work.”

It’s hard to argue the city’s water treatment plants wouldn’t benefit from decentralization (and, oh, I don’t know, maybe not sitting in a known floodplain that has historically flooded several times before?), but the price-tag affiliated with that option is prohibitively large. Some $2 billion per plant, according to the City. That’s in contrast with $65 million for the approved project – $22 million of which is coming from federal and provincial grants.

Politicians aren’t typically the type that garner much public sympathy, but this is one hot seat I wouldn’t want to be in. Scalp the river valley or risk drinking North Saskatchewan cocktails for a year? Either way, someone’s bound to be upset.

Savvy AF. Blunt AF. Edmonton AF.