The woes of downtown Edmonton are well documented: Office workers fled during the pandemic and many haven’t returned; empty retail space; construction everywhere; a semi-deserted vibe most evenings; the scourge of homelessness and addiction.

But what to do about them?

That was the question the Edmonton Downtown Business Association (DBA) was trying to answer when it invited two downtown-business-development professionals to town for a panel discussion with the DBA’s executive director, Puneeta McBryan. The occasion was the DBA’s annual luncheon – its first in three years – attended by 235 people at the JW Marriott.

McBryan had taken the two, Kate Fenske, CEO of Downtown Winnipeg BIZ, and Nolan Marshall, CEO of Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association, on a tour of Edmonton the day before. They began by providing their initial impressions.

“Every issue a city has is solvable, but you have to decide who you’re working with to solve it."

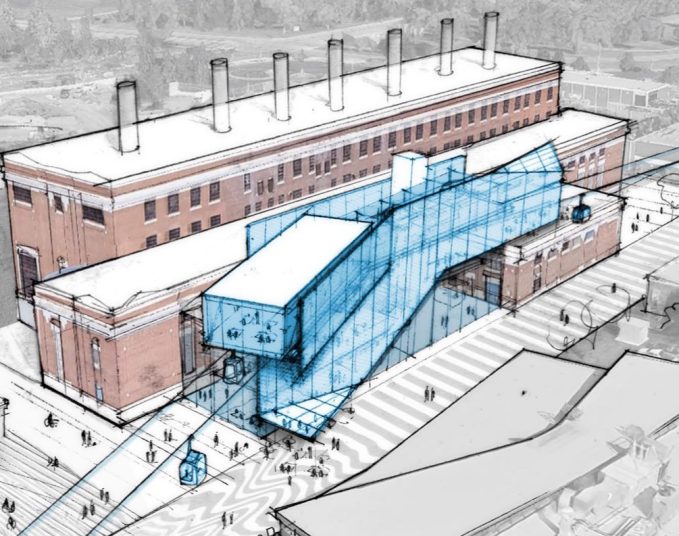

“I thought Winnipeg was quiet,” said Fenske, “but when we were walking around yesterday I was, ‘Oh, our comeback is happening a little quicker.” Marshall, an American who has worked in downtown development in cities across the United States and was named to his current job last year, said he was pleasantly surprised that he didn’t see more open drug use. Both were impressed with the City of Edmonton’s Warehouse Park plan, which will turn 1.5 hectares of surface parking between Jasper Avenue and 102nd Avenue into a multi-use park by 2025.

Marshall said the first thing to do when advocating on behalf of downtown development is to answer the question of why downtowns matter. The answer is simple, he says: economic growth. “Young professionals, the greatest asset in business attraction and retention, aren’t judging the community they want to live in by the quality of their suburbs,” he said. “They’re thinking about the amenities and attractiveness of downtown.”

He says downtowns need good jobs, quality places to live and streets that people feel safe walking. He says his organization contributes to making downtown welcoming by hosting events, supporting public art and employing “clean teams” to empty garbage cans and pick up litter.

He says we often treat the symptoms of our downtown troubles – street disorder, broken windows, people sleeping in doorways, rampant drug use – but we don’t get at the root problem, which he identifies as people who are disconnected from work and home. “The strongest correlation between increases in street disorder and homelessness is with housing cost and unemployment,” he says.

So, as a business leader, he advocates for and supports affordable housing and skills and jobs training. He acknowledges those mandates are way bigger than a business-improvement organization, or even a city, can manage. In fact, those are provincial and federal matters, “but all the issues happen in our areas,” he says.

Fenske says a large residential population downtown is crucial. Winnipeg now has 18,000 downtown residents, up from 14,000 in 2014. She says she doesn’t expect all the former office workers to come back, ever, and that Winnipeg is trying to turn its downtown from a central business district to a social gathering district, bringing more people in the evenings and on weekends.

In Winnipeg, they also created the Downtown Community Safety Partnership, a non-profit made up of leaders from business, government, and police and fire services. It has frontline teams prepared to respond to safety concerns and social disorder. Responses can include assistance and referrals, social needs assessments, advanced first aid, outreach and courtesy walks. “For us, where we see the opportunity is when everyone comes to the table together,” Fenske says. “Every issue a city has is solvable, but you have to decide who you’re working with to solve it and you have to commit to doing it.”

McBryan picked up on the cooperation aspect. She says Edmonton has some good structures and programs in place to help people get trained and into jobs, but that “we’re not coordinating funding and we’re not coordinating service delivery at the level that we need to to actually make a difference on the things we need to, like housing and mental health care.”

She agrees that the role of a downtown may have permanently changed in the face of the uncomfortable truth that people are coming into the office towers less often. “We have to start accepting it as the new normal and start thinking about what comes next,” she says. “What are the new businesses we can attract downtown? What about other organizations, like non profits or entertainment venues?”

Fenske mentions one recent development in her city along those lines. In April, the Hudson’s Bay Company transferred ownership of its landmark location in downtown Winnipeg to a First Nations group. That group, the Southern Chiefs’ Organization, intends to turn the 96-year-old, six-storey, 665,000-square-foot building into 289 affordable housing units, two restaurants, a public atrium, a rooftop garden, a museum and an art gallery.

“What do you want to be known for?” she asks. “What do you want to hang your hat on and say, ‘We are proud of this in Edmonton.’”

Savvy AF. Blunt AF. Edmonton AF.