Imagine this: You awaken on a Saturday. It’s your day off and the July sunlight is shining through the windows of your affordable, downtown Edmonton high-rise apartment greeting you and the other 1,200 tenants with a balmy 28 degrees Celsius.

You take the elevator downstairs and use the city’s underground pedway to beat the heat as you make your way towards the pedestrian mall that runs north along 102nd Street from Jasper Avenue. You grab a bite to eat at one of the many restaurants that fill the multi-level, semi-enclosed shopping arcade and spend the rest of the morning perusing the wares of some of Edmonton’s chicest storefronts.

After some satisfying window shopping, a friend calls. That person has just arrived downtown via a free shuttle bus and wants to meet for dim sum in one of Edmonton’s trendiest enclaves — Chinatown. You accept, and, as it’s outside of rush hour, you hop on the City’s free LRT service to get there.

After lunch, you decide to take a leisurely walk through historic Old Town along Jasper Avenue’s east block. Above the refurbished, Edwardian facades people sunbath and relax on their balconies overlooking the river valley. Nearby, people shop for groceries at Festival Market — an open-air market filled with farm-to-table goods.

As the day turns to evening, you head to the river valley’s recreational theme park nestled at the base of McDougall Hill, making your way through its art installations, attractions and performers.

Afterwards, you decide to take advantage of the evening’s cool air and walk home. It’s a long walk, but even at night the city feels safe and inviting. On your way home, you pass Churchill Square where a band is playing on the permanent bandstand. A little further southwest you make your way to Jasper Avenue, its median adorned with illuminated sculptures, foliage and lighted trees. You make your way back to your apartment and as you get into bed, the hum of a lively city centre slowly lulls you to sleep.

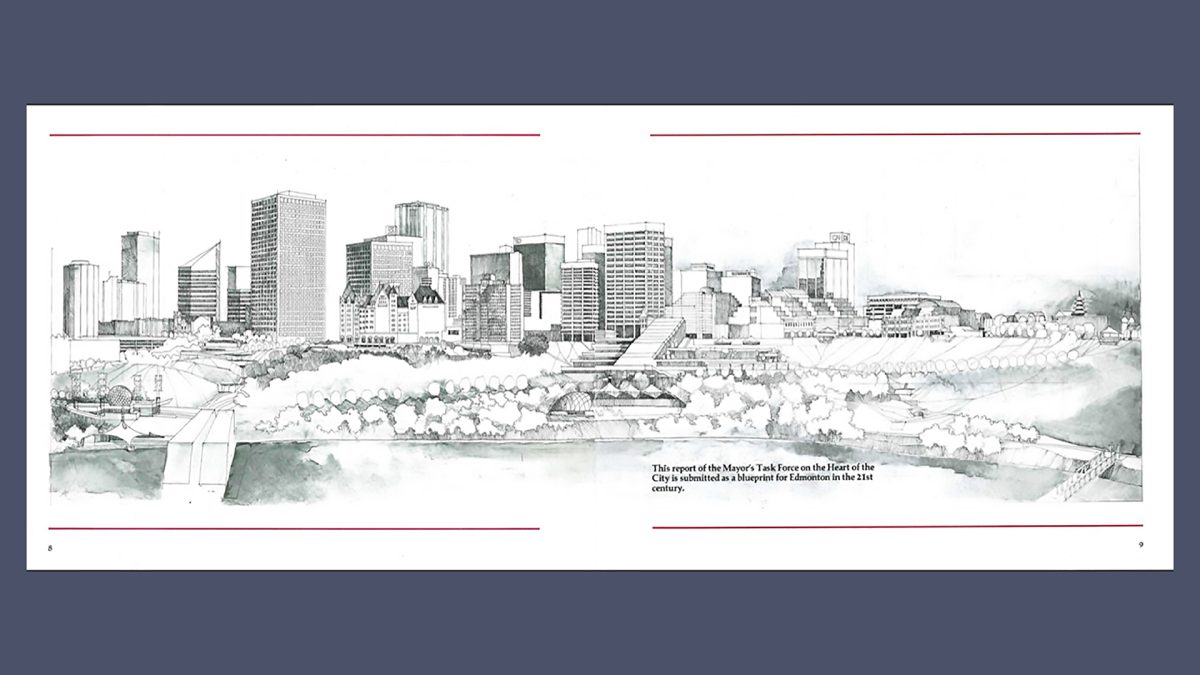

If there was an onomatopoeia for the sound of a record scratching, right here is where I’d put it. That lovely vision is not the downtown Edmonton we have today. But it could have been. The vision comes from a 40-year-old plan for revitalizing the city’s downtown, dreamed up by former mayor Laurence Decore’s Task Force on the Heart of the City and submitted to city council in 1984.

If you’ve never heard of it don’t beat yourself up. I hadn’t either. I’m guessing most people don’t keep tabs on each successive municipal development plan put forth by the City, let alone ones that are older than many of the staff working at City Hall today. But I happened to stumble upon an incredible ode to this period of municipal politics while surfing on YouTube.

Pretty incredible, eh? The twinkle-infused skyline. The kitschy music. The grainy video. The whole thing plays like a time capsule of things that could be used to explain the 1980s to an alien species.

Interplanetary dialogue aside, the video is promotional material for the task force’s final report (which you can read here). The report — dubbed a “blueprint for the 21st century” by its authors — was intended to be a roadmap that could turn Edmonton’s inner city into a world-class destination that other cities in North America would seek to imitate. But four decades and four city plans later, many of the issues the 1984 report talks about continue to be issues today. Things like safety, and the perception of safety, increasing residential density, attracting commercial and cultural institutions, education and effective transit are all things still present in the City’s current downtown revitalization plan.

For as long as I’ve lived here, revitalizing downtown has been a topic of discussion in the city — one that’s been accelerated in recent years by the impacts of COVID-19 and inflation. After reading this report, I wanted to understand how, after seemingly 40 years of trying, we’re still circling the same issues. So, I reached out to some of those who were involved in that 1984 task force to see what went wrong and what went right. The only problem? Most of those who drafted the report are, well, dead.

But former mayor Jan Reimer, whose administration came to power after mayor Decore’s, is very much alive and well. So, I sat down with her to ask what happened to the recommendations made in the task force and why she thinks we’re stuck tackling the same things her council dealt with.

“Some of the things happened,” Reimer says. “The Jasper Avenue improvements came and went … and we did get the concert halls built.”

Reimer’s right. Not everything from the report failed to materialize. Churchill Square and the surrounding theatre district look the way they do in large part because of this report. MacEwan University also owes a great deal to the vision set out in the report as does the vibrant 104th Street and the (somewhat) unique aesthetic of 108th Street (though the report claimed there would be statues of former premiers along that boulevard). There was even a period in the 1990s when parts of the city’s LRT service were, in fact, free (during non-peak hours). But the truly visionary, big stuff failed to get through.

“When I was elected, [Ralph] Klein was premier and we were getting multi-million dollar cuts,” Reimer says of why some of the report’s more grandiose ideas never bear fruit. “It seemed like they were cutting everything.”

There was also the issue of a smaller Edmonton back then, one that the council of the day was worried might not be able to support the type of vision the mayor’s task force suggested. That was particularly evident with the proposed Festival Market, which Reimer says was scrapped due to the belief that it wouldn’t be able to compete with the Old Strathcona Farmers’ Market.

“There was all sorts of desire to have a downtown market,” Reimer says. “But in the ’80s there was a real downturn in the economy and this question about whether we could sustain — did we have the population to support — two big markets was the debate at the time.”

Analyzing the demise of each and every proposal in the report would take more time and space than my editor would possibly allow, and the minutiae of 40-year-old bureaucracy can be a challenging language no matter your length of study. But that’s largely irrelevant, because, for Reimer, the reason a vibrant downtown has eluded us thus far comes down to one thing: housing.

It’s the same old drum that advocates have been banging on for the better part of the last four years. How we get people to not just visit, but live, downtown?

“For a vibrant downtown, you need people downtown and to have people downtown you need to have places where they can live and not just hangout and leave at the end of the day,” Reimer says. “Where we have not been able to see great success is around downtown housing.”

But it’s not for a lack of trying. The task force’s report suggests building plenty of housing in the Jasper Avenue East Block, which today is largely vacant and boarded up, and on the lands that formerly housed the Canadian National and Canadian Pacific rail yards. But Reimer says development pressure and politicking led to a different outcome.

“Council several times … changed zoning from residential to commercial,” Reimer says. “So instead of higher density housing we ended up with London Drugs, Safeway and a lot of car-friendly shopping but not necessarily pedestrian-friendly ways of bringing people downtown.

“[There’s] developer pressure to do that … political pressure. There’s wanting a tax base. It’s hard because of financial pressures, but you really need to have a long-term view and sometimes there’s a lot of development pressure to say ‘let’s just get something done’ as opposed to ‘is this in the best interest over the long-term?’ People want to be able to point to what they’ve done.”

But even with pressure, the city has made progress in the years since the report was tabled. In 1984, downtown had roughly 4,500 housing units. As of 2023, it boasts more than 15,000 units according to the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation, 3,915 of which have been build since 2010, according to the City of Edmonton. But the City has not issued a residential building permit for downtown since 2021.

The Edmonton Downtown Business Association reports there are about 13,000 permanent residents in the core today.

The employment base, which was then 61,000, was predicted to grow to 100,000 by 2004. It’s now closer to 105,391, according to the City’s 2023 business census. Large-scale projects, most notably the ICE District and Rogers Place, have come to fruition even when the report’s fantastical theme parks and pedestrian malls haven’t.

Tom Girvan, the City’s director of downtown vibrancy, said the City’s efforts to bring an imitable, world-class downtown to Edmonton are still very much alive and evidenced by some of the strides the City has made in recent years.

According to the City’s 2021 downtown vibrancy strategy, there’s been some $4.4 billion in downtown development, with more than six million square feet of buildings constructed across a variety of strata including 2,400 residential units, commercial, cultural and others buildings.

Girvan said that while eyeing up the past can be important in building current day plans for the downtown, the goalposts of yesterday don’t always match the needs of right now.

“These are living, breathing places,” Girvan said. “You need to be flexible to the opportunities of the day and nimble as to how you support growth and investment in the city both today and in the long-term when it comes to these plans.”

Savvy AF. Blunt AF. Edmonton AF.