Last September, a teenaged boy was hospitalized and another charged with assault after a fight at Queen Elizabeth High School. Two weeks later, two teens were ticketed following a dramatic lunchtime brawl in Londonderry Mall. Both these stories were caught on video, and both videos were shared with Yegwave, an anonymous Instagram account, which broke the stories.

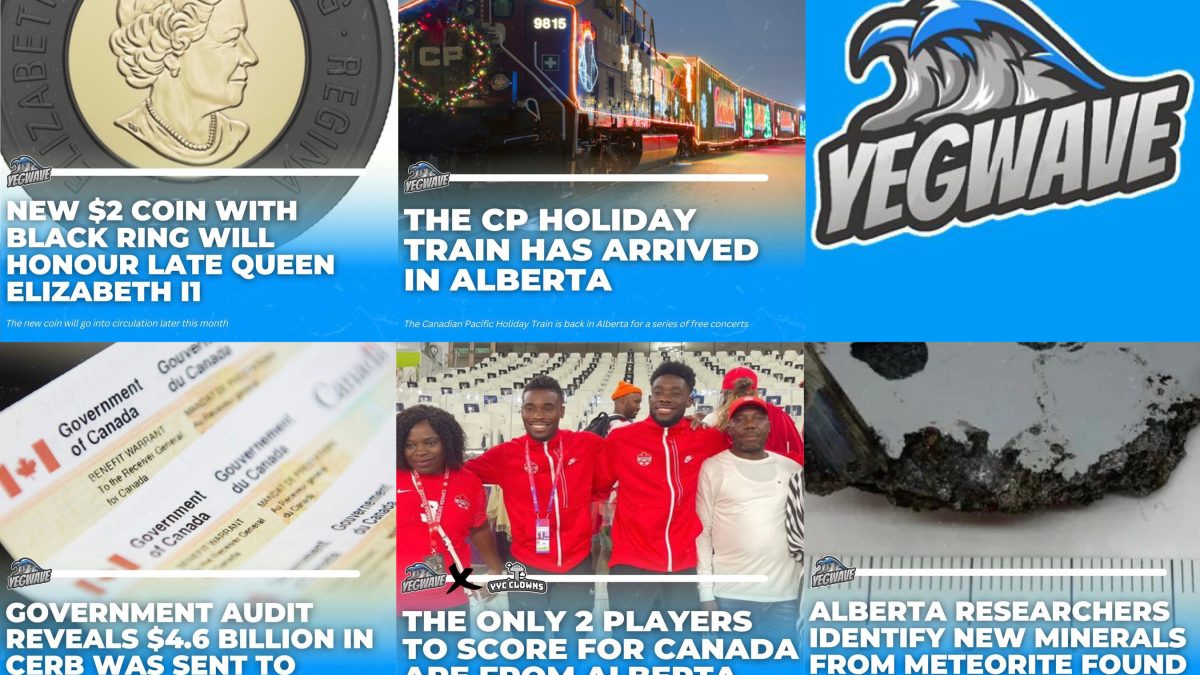

Billed as the “#1 Alberta Entertainment Page,” Yegwave launched in March 2020 at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, and has amassed more than 148,000 Instagram followers – more than any of Edmonton’s major media outlets.

The feed is a mix of news aggregation, breaking stories submitted by followers, and amusing footage of things happening around the city. Geared toward teens, its headlines are posted in a distinctive, all-caps style with photos and brief, caption-length stories written in Gen Z-friendly language.

“They're in school, they're in university, they’re out and about, and they’re sending us things that they see."

“They feel like it’s someone in their age group posting the news, and I think that’s what’s so appealing to people. It could be one of them or someone they know,” says a Yegwave founder, who agreed to speak with Urban Affairs on condition of anonymity. “It’s authentic. It’s not some 40-year-old man posting news.”

While most of Yegwave’s content is gathered from other sources, sometimes posted within minutes of another news outlet breaking a story, the account has struck gold engaging youth. The fight videos were submitted by followers, and the founder says Yegwave gets 10-20 content submissions a day from people in the 12-18 age group, which would be unheard of at a newspaper.

“They’re in school, they’re in university, they’re out and about, and they’re sending us things that they see, things that they might not send the news or that news organizations might not pick up on so fast,” he says.

“We’re getting that information first from the people who are outside.”

Brian Gorman, a former journalist and current communication studies associate professor at MacEwan University, appreciates the way Yegwave’s Instagram feed swaps the hierarchy of the traditional news layout in favour of a more stream-of-consciousness approach.

“I found myself scrolling and scrolling and scrolling because it’s addictive. You don’t know what you’re going to find next,” he says. “I mean you’ve got a news story, a sports story, an entertainment story and then a picture of a woman in an evening gown jumping over a snowbank.”

Gorman is reluctant to call what Yegwave does “news,” but says he doesn’t see an ethical problem with the way the page operates generally, saying it’s not far from the origins of outlets like the Huffington Post, which started as an aggregator.

He suspects most of its followers are smart enough not to take it as their be-all, end-all information source.

“I teach Gen Z,” he says. “My students are all 18-30, and I’ve never gotten the impression that any of them were dumb enough to confuse Twitter or Instagram with the New York Times.”

According to an American Press Institute study published in August, 74 per cent of Gen Z consumes news through social media, while 44 per cent don’t get news and information from any traditional sources.

The founder says Yegwave was never intended to make money, despite the work his team puts into keeping it current. The page occasionally posts paid promotional content – a gift card giveaway or a new music video by a local rapper, for example – but has no immediate business plan beyond that.

“When people start to feel like it’s another news corporation and a really official business, it starts to feel less authentic,” he says.

“We don’t have to appease a network or advertisers. We don’t have to worry about a larger company controlling or moderating our content.”

Yegwave is also active on TikTok, Twitter and YouTube, but does not have a standalone website or its own reporters and will not say how many people are behind the account. The founder would not reveal their ages either, except to say they are not high school students.

But without the checks and balances of an established news network, the account wades into some legal and ethical grey areas. Canadian news organizations typically adhere to stringent rules to protect minors in adherence with the Youth Criminal Justice Act, for example, which prohibits identifying young people who have been charged with or victimized by a crime. The fight videos, which are still up on Yegwave’s Twitter account, could be ethically problematic, if not legally.

A video is not as cut-and-dry as naming a young offender, as one could argue the chaotic smartphone shots don’t clearly identify faces, but Calgary-based media lawyer Scott Watson says Yegwave is “perhaps treading on a fine line.”

“The major traditional news outlets have standing counsel who advise them frequently on what those limits are and what can and can’t be produced and it’s part of the restriction, part of their practice guidelines,” he says.

“The openness with which communication and publication occurs, I think, does attract groups that don’t have the established connections with lawyers and the understanding of what these restrictions are, and so it’s a little bit more wild west in their approach to publication.”

Going official as a serious media outlet would mean stepping up accountability and revealing the identities of those involved in publishing, and the founder feels the strength of the audience connection hinges on anonymity.

“I think people are more comfortable submitting things to us when they think it’s a faceless entity,” he says. “Suddenly when your face is plastered it becomes personal and people are scared, ‘Well, what if this person reveals me as a source?’”

While that might sound counterintuitive, investigative journalist and University of Victoria professor Sean Holman says it fits with a growing distrust of professionalization. He says many mainstream media outlets are similarly developing a “chattier tone” in their reporting and trying to align with their audiences on a cultural level.

“It speaks to how other types of voices are being prioritized in our society. The personal voice, the casual voice, the voice that sounds like someone you know seems to be winning larger audiences,” Holman says.

“It’s interesting that the tone of the voice is the thing that is determining the trust, not whether or not you can identify the voice.”

Yegwave’s conversational tone extends to the comments; its posts regularly have hundreds of people weighing in with uncensored takes. Maria Bakardjieva, a digital media expert and chair of communication and media studies at the University of Calgary, suspects this is a big reason for the account’s popularity, and also a reason to be wary of the anonymity.

“People who go there to comment, they build their own community, they build their own culture. And for young people, that’s particularly important because for them, peer interaction is huge,” she says.

“If any misinformation, if any conspiracies, if any fake news is to make its way into a site like this, it could do a lot of damage. Especially if young people have recognized it as their own, as their place to go. That is what makes it critical who really runs it, and with what kinds of ethics and responsibility they do it.”

On the flip side, Bakardjieva says this type of engagement can encourage followers to get more involved in their communities and expand their political knowledge beyond what they see on social media. She says Yegwave appears to strike a healthy balance by mixing teen-friendly content with news that people in their age group might not otherwise flock to.

“Anything that can meet young people somewhere between these completely unverified stories they may encounter on their friends’ profiles, and the responsible journalism media, is welcome and should do them good,” she says.

Savvy AF. Blunt AF. Edmonton AF.