Five years ago, a few months prior to her death at age 77, I sat across from the legendary Cree activist Lillian Shirt while she ate a spicy hot pot. In 1969, having been evicted from her Edmonton apartment and unable to find a landlord to rent to a single, Cree woman with children, Shirt set up her grandmother’s tipi in Winston Churchill Square, in full view of the mayor’s office. Her protest lasted 12 days, during which time she was joined by others and met with then-mayor Ivor Dent and then-premier Harry Strom. Her desperate act attracted news coverage from across the country and has been credited with kickstarting a provincial plan for welfare housing.

I was interviewing her for an article I was writing, although it was less of an interview than a conversation punctuated by her soft laughter. The day before I met her, she’d presented a Bent Arrow Coyote Pride talk to a classroom full of kids, something she did regularly. One girl asked what learning was like when Shirt was young. Shirt told the class about Indigenous traditions, but she told me those traditions stopped for years when she was five years old and went to residential school. She didn’t like talking to the children about that, she said, “because it would be like talking to you about it. It’s not your bad dream; it’s my bad dream.”

She was right. It was different from anything I knew as a great-granddaughter of settlers. I grew up in an area where settler culture dominated. Indigenous people were presented as anachronistic; they’d lived and thrived long ago. There was little recognition of the extensive knowledge they had, and no acknowledgement of the contributions of Indigenous people. My Ukrainian ancestors tamed land that had been previously unoccupied. Or so we were told.

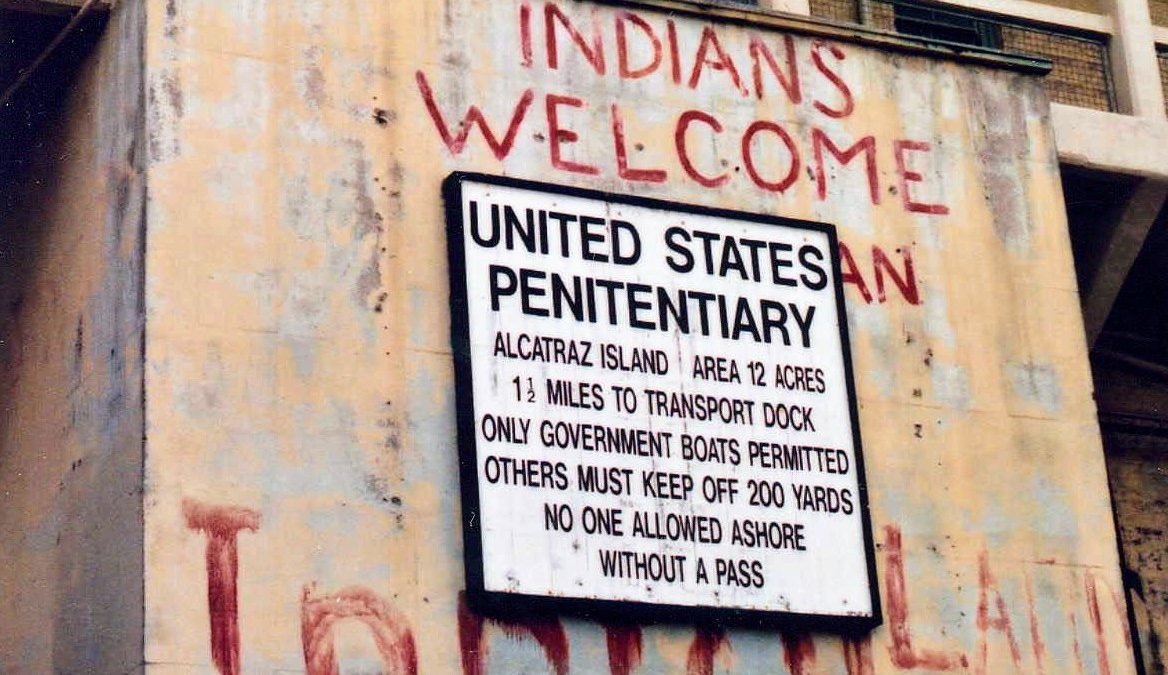

Nearly everything Shirt said caused my jaw to drop. After the tipi-in-Winston-Churchill protest, she founded the Alberta Native Peoples Defense Fund to provide legal aid to Indigenous men and women. In 1969, she took part in the 19-month occupation of Alcatraz Island, in San Francisco Bay, by Native Americans who argued that it had been taken in contravention of a treaty. Following that, she lived for years in the Kootenay Plains at the Smallboy Camp, founded by Chief Robert Smallboy to draw attention to the terrible conditions many Indigenous people endured. She also said she had spoken with John Lennon during her tipi protest and, in a twist of history so unbelievable it might just be true, she may have inspired lyrics in his immortal song, Imagine.

“It’s an essential part of settler culture to not recognize Indigenous involvement and to prioritize the Canadian nation and nationality instead, as though one cancels the other out.”

Shirt had taught countless children about Indigenous culture over several decades, maintained knowledge of medicine and art over generations, and, now, she was teaching me.

The Context

In the late 1800s, Shirt’s great-grandfather, Kapapamahchakwew (Wandering Spirit), was a Cree war chief who lived in what’s now Saskatchewan. Like Shirt, he was strong, independent and a fighter. Like Shirt, he made history, although the history books usually focus on the violence of Kapapamahchakwew’s story, with little context.

Bison had been the main source of food, clothing and shelter for Indigenous people from time immemorial. By 1879, the great bison herds were gone from the northern plains. South of the border, bison were deliberately killed to push Indigenous people onto reserves. The Canadian government used the bison’s collapse to pressure Indigenous people to agree with settlement plans.

Kapapamahchakwew joined Cree Chief Mistahimaskwa (Big Bear)’s band because he agreed with the leader’s position on treaty negotiations with the Canadian government. At the time, Treaty 6 was being negotiated between the Crown and various Indigenous groups, making its way westward from Hudson Bay. Mistahimaskwa didn’t believe the government was offering enough or would live up to its promises, and he was right.

Treaty 6 said Indigenous people would receive assistance if they experienced “pestilence or general famine,” but despite having lost their primary food source, many did not receive rations or, if they did, the food was often rotten or nutritionally insufficient.

John A. Macdonald, prime minister at the time, said in the House of Commons in 1882, in response to questions from the Liberal opposition about money being spent on rations for Indigenous Canadians, that his government was keeping them on the “verge of starvation” to keep costs down.

“I think one of the things we have to recover from the influence of colonialism is the opportunity to be human beings together”

Mistahimaskwa’s band was among the starving. He was resistant and therefore his band did not qualify for rations. “He’s essentially starved into entering a treaty in December of 1882,” says historian Bill Waiser, co-author with Blair Stonechild of Loyal Till Death: Indians and the Northwest Rebellion.

Mistahimaskwa’s people were told to move north, to the Frog Lake district, where a reserve would be selected for them. That was also a treaty violation, says Waiser, because under the agreement bands were supposed to choose their own reserve.

They were only fed if they followed horribly restrictive government directives. So they continued to starve under Indian agent Thomas Quinn, who was especially harsh and reviled. “So again Indigenous people like Wandering Spirit are chafing under this government coercion and interference,” says Waiser.

There was desperation, disease and starvation, along with deep distress around unmet treaty promises.

In 1885, Kapapamahchakwew was at the helm of the Frog Lake killings. At the time, Louis Riel was leading the North West Resistance (as it is now commonly called), concerned about the federal government’s treatment of the Métis. He led a series of armed battles, ending with him being branded a traitor and hanged.

The Frog Lake killings stemmed from similar sentiments about treatment of Indigenous Canadians, but Waiser says Frog Lake was not on the same scale. “It’s a targeted attack against people in authority – the Indian agent, the farm instructor and the priests are killed,” he says.

Kapapamahchakwew captured nearby Fort Pitt and let the mounted police withdraw. “This camp of prisoners eventually grows to several hundred. But they stay in the area,” says Waiser. “They don’t join Louis Riel, they do not carry out offensive activity, and they wait to see what evolves.”

The group eluded capture for months before surrendering. Eight were hung in public, including Shirt’s great-grandfather, without having had the benefit of legal representation. It was the largest mass hanging in post-confederation Canada. “The executions of the Indians ought to convince the red man that the white man governs,” Macdonald wrote to his Indian Commissioner, Edgar Dewdney.

Waiser says that, prior to 1885, Indigenous people, mixed-race people, and white settlers lived, worked and traded together. Things may not always have been peaceful, but having Indigenous connections, says Waiser, was a huge benefit to newly arrived settlers with no knowledge of the land.

My family has its own story. My great-grandfather occasionally made a three-day trek from the country to the city for supplies. On one such trek, he was carrying supplies on a raft along the North Saskatchewan River when the raft fell apart. He approached some homesteads but no one would take him in, he said, because he did not speak English. As he neared hypothermia, Indigenous people took him home where they fed and warmed him.

My family’s story, if we listen hard enough, is echoed across the prairies, particularly in light of the war in Ukraine. Now, people are speaking of the friendships and relationships common amongst the two cultures and of shared bits of culture like kokum scarves.

They’re great stories that make us feel good. But they don’t tell the full story of what happened next or the settler’s role in colonization. My relatives faced discrimination initially – Ukrainians were seen as inferior to others in many cases – but, over time, they found their place in white settler society.

Meanwhile, after the resistance, many of Shirt’s relatives became refugees in a group of a few hundred, fleeing Canada for the U.S., fearing further punishment and the enforcement of draconian measures.

“In my opinion, 1885 represents a watershed year in western and Canadian history,” Waiser says. “After 1885, there was an emphasis on whiteness. The society in Western Canada was to be Anglo-Canadian Protestant.”

Indigenous people were isolated and their movement restricted through the pass system, which required Indigenous people to present a travel document to leave or return to their reserves. Spiritual practices were banned; they could not sell produce without a permit; they could only work fields with hand tools, not machinery.

Those in power knew the resistance represented a small percentage of the population, so it would be inaccurate to say that the fighting solidified pre-conceived notions that authorities already had. Waiser says there is enduring prejudice, felt until this day, “that First Nations cannot be trusted.” According to this bias, Indigenous people should be feared, and kept separate, as they’re pre-modern people, he says.

The Gaps

“I identify colonialism as an extended process of denying relationships,” says Dwayne Donald, a professor in the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Education and a descendant of the Papaschase Cree.

“You can’t displace people from their land if you consider them your equals,” he says, “so what we see in the late 1800s is a serious ramping up of racist rhetoric.” He mentions the university’s extensive digital curricula archives, so I go online.

Within a minute, I find a social studies textbook, Canadian Savage Folk; the Tribes of Canada, first printed in 1896. It presents Indigenous beliefs and ideas as primitive, something foreign to be critiqued and studied. Europeans, says Donald, were studying people that weren’t like them and arbitrarily forming racial, gender and class categories based on what they believed was innate intelligence.

That’s what my ancestors would have been learning about in official curricular resources: straight up, unabashed racism and prejudice that continues to reverberate through our country.

“It’s an essential part of settler culture to not recognize Indigenous involvement and to prioritize the Canadian nation and nationality instead,” Donald says, “as though one cancels the other out.”

Think of the stories you were told in school – images of forts and the North-West Mounted Police come to mind. Stories that involve “power, control and the exploitation of resources,” says Donald. Throughout his research, he’s considered the fort as the symbolic heart of Canada’s creation story. Initially, the walls were permeable, but there was a drastic shift when attention turned to the land. At that point, the fort separates and excludes Indigenous people from the rest of Canada, Donald says.

It wasn’t until 2021, when the remains of 215 children were found buried at the Kamloops Indian Residential School, that I truly began to recognize the integral role residential schools played in Canada’s nation building.

“Part of the national mythology is this claim to sovereignty that Canada made over this land,” Donald says. “That’s a big part of all the institutional rhetoric we hear in education. If Indigenous people are considered part of the land, then if Canada owns the land, they own these people. They can own them to the extent that they could own their language, their spiritual practices that are still stuck in museums. They could even own their children.”

Children were forcibly taken from their parents to a place of deep trauma. In 1907, Dr. Peter Bryce, the chief medical officer for Indian Affairs in Canada, wrote the first of several reports drawing attention to the desperation at residential schools. He found that more than 90 per cent of students suffered severe physical, emotional and sexual abuse, and that the mortality rate was between 40 and 60 per cent.

Children were often referred to by a number, not a name. There are survivors who saw the dead bodies of murdered classmates. Some dug graves for the dead. Many children died of illness and many died trying to run away.

Even those that lived often didn’t go home for many years. Shirt spent two years in Edmonton’s Charles Camsell Indian Hospital with tuberculosis, a disease that killed a disproportionate number of Indigenous children.

Residential schools had such poor nutritional standards and such a lack of funding, the children couldn’t fight the disease. Bryce asked for change but the government was steadfast in its desire to “kill the Indian in the child.” The government green lit experiments in which the children’s malnutrition was used as a baseline for testing various measures like adding fortified flour to their diets, often resulting in anemia. In 1922, after years of inaction, a frustrated Dr. Bryce published The Story of a National Crime: An Appeal for Justice to the Indians of Canada.

The malnutrition resulted in immediate and long-term health complications. Over time, some people tried to argue these issues – from a higher risk of type two diabetes to stunted growth and susceptibility to deadly illness – were genetic. But they were the result of deliberate neglect. Abuse also led to devastating intergenerational physical and mental health effects.

Hospitals like Charles Camsell were part of these crimes, although Shirt said she was treated well by staff. She told a story of a kind nurse who paid for her distance learning, and that’s what made it into my article.

But she also said: “I wonder if I really did have TB, or if they were just doing experiments on me. I never did find out.” She had stayed there for two years without seeing her family. She couldn’t even walk around – she had to be constantly resting. Those details should have been in my article.

Shirt’s Legacy

Andrea Watchmaker of Bent Arrow Healing Centre worked with Shirt, who was the elder for the Coyote Pride program, for 13 years.

“From the first time I took her to a school, I thought: Wow, she’s got to come back,” says Watchmaker. “She was very, very good.”

Shirt came back and then just kept coming, often on a weekly basis, sometimes more, to speak about land-based teachings, Cree language and traditional ceremonies to young children. She’d even camp out with the children and smudge and pray with them.

Just a few weeks before her death, Shirt delivered one more talk; she spoke of Indigenous medicine, without mentioning her own illness. She was so full of life that her death came as a huge surprise to everyone, even her granddaughter, Kathryn Chodzicki.

Chodzicki now works with Coyote Pride. On her first day, she was nervous to start in the role of Indigenous program leader for the program. She looked up, and there on the wall was a giant photo of her late grandmother. Chodzicki knew Shirt taught children, but didn’t realize it was through Bent Arrow. “She was so humble and so in the moment spending time with us, she wouldn’t talk about herself or the work she was doing,” says Chodzicki.

Chodzicki didn’t learn the full extent of the horrors of residential schools or Indigenous day schools or the ’60s scoop when she was a child. But when she did, through her social work program, she was inspired to follow in her grandmother’s footsteps. She just didn’t realize how closely those footsteps would align.

Chodzicki is happy teachers now engage with foundational knowledge of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit, regardless of what subject area or level they teach. That means hopefully more young people will now more fully learn the history of Canada.

But, she says, she’d like to see more. Her grandmother was passionate about bringing Indigenous culture to children, and she’d like to see that happen in all schools. “There need to be more Indigenous worldviews brought into the classroom. Not just highlighting the history and injustices, but bringing in voices authentically,” says Chodzicki. “It takes a co-existing relationship between Indigenous people and these systems.”

Chodzicki also worries the classrooms are not exploring the current issues in society. “There are survivors [of the residential school system] that are still alive that have children in schools that are dominated by western ideologies,” says Chodzicki.

Alberta’s new K-6 curriculum has been poorly received by many teachers and parents. They say it white-washes history and does not adequately include Indigenous history. “Curriculum is much more than just listing off topics to study,” says Donald. “It’s really an expression of world-view. I consider it a sacred type of work because it really has to do with the stories we want to tell children about the world.”

Outgoing Premier Jason Kenney has defended the curriculum, saying it’s a “back to basics” approach that gets away from “divisive woke-left ideology like critical race theory.” It’s a conversation that is mirrored around the globe, particularly in the United States where some states have banned the discussion of critical race theory – an examination of the ways racism informs public policy – and topics related to LGBTQ2+.

“I mean, it’s pretty obvious that race is associated with power and control and if you want to maintain power and control you don’t want people to talk about it,” says Donald.

The K-6 curriculum focuses on classics of western science and literature. Students memorize facts like the year 1885 as the North West Resistance. But educating students takes more complex approaches, says Donald. He says the new curriculum presents Indigenous people in the past and puts settler stories at the centre while dividing people from each other and the land. It sounds similar to what I learned; basically, it comes back to those images of “power, control, and the exploitation of resources.”

If Donald were to distil the message behind the curriculum into a simple sentence, it would be: We are humans driven by consumerism and profit. That’s a sobering thought especially given the challenges we face with existential threats like climate change, which require a shift in perspective.

“To really address climate change, we would need to start a different trajectory,” says Donald. “It’s a spiritual and cultural problem, not a scientific or technical one.”

Colonialism, Donald explains, doesn’t just destroy human relationships, it creates a disconnect between people and the land.

Currently, the curriculum presents anything beyond western viewpoints as extra, but Indigenous perspectives are valuable to everyone. Indigenous culture does not see land as a commodity; rather people are connected to it. And a huge amount of wisdom stems from that connection – knowledge of plants as medicine, of climate and food, and of stories of living well together. Studying worldviews where the ecosystem is connected to the knowledge system could help create stronger connections to nature, food systems and even one another. It could shift cultural perspectives in a positive way.

“I’m not against what’s going on in schools right now necessarily but my question is what is missing?” says Donald. “I would also be very interested in getting students a chance to be outside and getting them to engage with knowledge in ways that are more informed by wisdom knowledge of the area.”

Colonialism is a shared inheritance, says Donald. Former federal politician Frank Oliver, whose name adorns a number of things in Edmonton, is villainized for his racism – for good reason, Donald says – but people re-elected him multiple times. Prejudice is embedded in our society and that’s what kids should be learning about. There should be more thoughtful and complex discourse, more self reflection.

Intergenerational Prejudice

Corinne George’s MA thesis focused on aboriginal women activists including Shirt, in part because she saw how underrepresented and misrepresented they were in history and literature. That lack of proper representation stems from what she calls “intergenerational prejudice” – bias and perceptions passed down from previous generations. She lives along the Highway of Tears, a 725-kilometre stretch of highway in northern B.C. that has a traumatic history of Indigenous women being murdered and going missing. “What happened to those women? Where are they? For me, no matter what the causes may have been, it is based at least in part on prejudices of who Indigenous women are and views that have been passed on from earlier perceptions,” says George.

She adds that racism persists in the judicial system. In May 2022, more than 65 per cent of inmates at the Edmonton Institution for Women were Indigenous, and nearly 60 per cent of men at the Edmonton Institution were Indigenous. Only 6.5 percent of Alberta’s population identified as Aboriginal in a 2016 Stats Canada report. All systems from health care to education are impacted by intergenerational prejudice and you can see those impacts reflected in poverty levels, disease rates and illiteracy among Indigenous people.

Antidote to Colonial Logic

“I think one of the things we have to recover from the influence of colonialism is the opportunity to be human beings together,” says Donald.

Treaty is the perfect antidote to colonial logic, he explains. And it has been a massive curricular omission. “Very few people have learned anything about it and if they do it’s that very problematic contract version about ceding land and surrendering this and that,” says Donald. “That kind of version where some people pay taxes and some people get stuff for free, which is such an awful violation of that agreement, what our people call a sacred covenant.”

Many Indigenous people saw treaties as adoption ceremonies where everyone was to adopt one another as relatives, look after one another, help one another, and teach each other’s children. So, it was about working together for mutual benefit. Those hopes were not realized but Donald has hope going forward. We can honour one another and renew relationships – tell a new story to our children of how to live well here, he says.

“An ecosystem needs that kind of difference for it to be healthy. There is no requirement for everybody to be the same,” says Donald.

Shirt knew how to live well and maintain relationships of all stripes. She was known by countless people, young and old, as Kokum (Cree word for grandmother) Lillian. She treated children with as much respect as adults and they loved her in kind. When I was driving her home after our last interview, she saw I had a photo of a matryoshka doll as wallpaper on my cell phone.

“You’re Ukrainian?” she asked.

When I said yes, partly Ukrainian, she smiled.

“Nice,” she said.

I went home with the strong desire to represent Shirt well in that article. I also wanted to tell the truth. So I spent a huge amount of time trying to confirm whether she had indeed spoken to John Lennon.

As the story goes, Lennon was staying in Toronto after hosting a bed-in in Montreal and had heard about her activism. He called a local radio station and requested to speak with her. The radio station couldn’t confirm it. I searched for something hinting Lennon had been inspired by anyone other than Yoko Ono. I even attempted to reach Ono, to no avail.

What she told me was that she had shared the words of her grandmother – the same grandmother whose tipi she had set up in Winston Churchill Square – with Lennon: “Keespin esa Kasakehetoyah, Kasetos-katoyah, Kawechehetoyah, Namoya Ka-no-tin-to-nanhoyo.”

“If we loved each other, if we supported one another, if we helped one another – we would not fight each other.”

For the record, I believe her story. It aligns with what was happening at the time. There’s no doubt Lennon would be interested in her work – they shared worldviews. Shirt spoke with Lennon once. It’s very possible she inspired him. But regardless, she inspired countless others.

That story was a footnote in Shirt’s life.

I missed the story, and I missed the truth.

The truth is I am a non-Indigenous person and my conception of our history and culture has been clouded by years of colonial narratives starting in school curricula and continuing in everyday life.

Not only did I spend far too much time chasing something that was a minor part of her story, I missed key details that would have helped show the extent of the prejudice in our systems and our culture. It was all there; I just didn’t see it.

Savvy AF. Blunt AF. Edmonton AF.