In Canada, the average life expectancy is around 82 years. Advancements in the field of health care have bolstered that number by about 22 years over the last century. But not everyone is in a position to benefit from those technological boons. For those of us in Canada facing homelessness, addiction or other marginalizing conditions, the numbers on life expectancy haven’t moved very much at all in the last 100 years.

That’s a colossal failure, according to Dr. Jeffrey Turnbull, a co-founder of Ottawa Inner City Health (OICH). OICH offers healthcare tailored to the needs of those living rough on the streets of Ottawa and was created by Turnbull and his colleagues after they saw the inability of established health-care providers to meet the needs of Canada’s homeless population.

Turnbull, the former chief of staff at Ottawa Hospital and previous medical director for OICH, was in Edmonton Thursday. He was part of MacEwan University’s Chancellor’s Speaker Series, talking about the successes of OICH and the importance of widening a transformational approach to health care that is more equitable than present-day offerings.

“It’s their needs — the community’s needs,” Turnbull told a capacity audience at the Robbins Health Learning Centre.

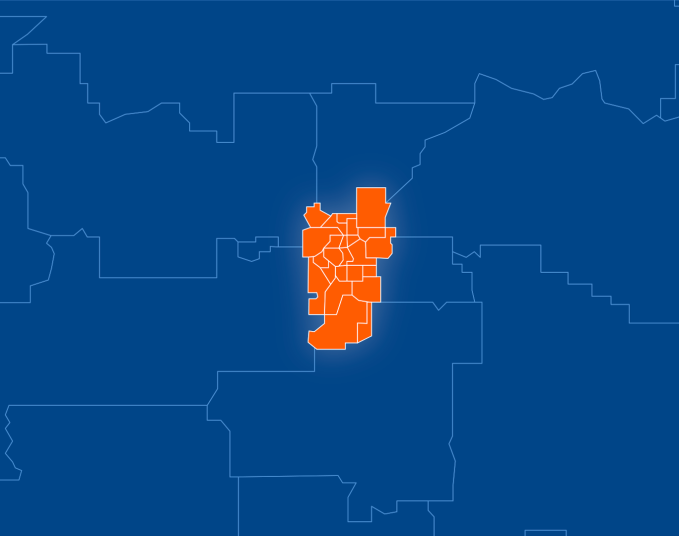

Edmonton is home to over 2,900 homeless individuals, according to the new Vital Signs report from the Edmonton Community Foundation. The majority of them are sleeping outside of shelters. Turnbull says for many of those people, health care is neither accessible, equitable nor accountable.

“I think everyone recognizes that the social determinate of health are inequitably distributed,” Turnbull said. “But I don’t think everyone would recognize just how massive [that inequity] is.”

In Canada, the average age life span of a chronically homeless individual is 62 years old, 21 years less than the national average.

“You can challenge these inequities. It just requires you be willing to break a few rules and listen to that community and respond appropriately to their needs, not yours,” Turnbull said.

For OICH, that meant bringing health care to the shelters and meeting patients suffering from addiction and mental health concerns — both of which can be contributing factors to homelessness — where they were.

In the years since OICH began, it has opened palliative care facilities, five supportive housing operations and programmed into its operations safer supply for both opioids and alcohol. It’s about understanding that there isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach to the health-care concerns most affecting vulnerable populations, according to Turnbull.

That’s not been the case in Alberta, where the provincial government has been ironclad about its commitment to a recovery-only approach to substance use disorders, refusing to consider options like safer supply and tamping down on harm reduction in Alberta.

Those policies are impediments to change, Turnbull said while answering questions from the audience, but said they can be overcome.

“You have to show them that what you’re doing is actually going to save lives and money,” Turnbull said. “Most governments will listen when you mention that last thing.”

And he’s not wrong. The current state of Canada’s homelessness crisis is expensive. It costs the national economy $7 billion annually, with institutional responses like shelters, hospitals and prison systems costing upwards of $50,000 per person, per year. Supportive housing, on the other hand, is tallied at between $13,000 and $18,000 per year.

“I think we need to make this financial argument,” Turnbull said. “We can’t afford to keep this outcome.”

Savvy AF. Blunt AF. Edmonton AF.