If you’ve been inside Rogers Place for a hockey game, a convention or a concert, there’s one thing you can’t deny. It’s big. It occupies over 1 million square feet.

Now, imagine taking another Rogers Place and placing it on top of the one already there. And then another. And another. Keep doing it till you’ve built a tower that’s 18 Rogers Places high.

What do you have? Something that’s about equal to the total inventory of commercial space that’s in downtown Edmonton. According to the latest quarterly report from Canadian commercial real-estate giant Avison Young, Edmonton’s commercial downtown vacancy rate is at 20.4 per cent, the second highest of any Canadian major centre. The ideal rate is about eight per cent — it allows for those looking to lease to have choice, but doesn’t put all sorts of undue pressures on landlords to offer too-good-to-be-true deals.

“The numbers are troubling, they are high,” said Cory Wosnack, Avison Young’s managing director for Edmonton. “Calgary sets the high water mark for a very unsustainable vacancy rate — thirty per cent or greater is just traumatic, but a 20 per cent vacancy rate is still very high. What we need to get to is a balanced vacancy rate.”

That’s right — Calgary has been leading the way in vacancies for a couple of years, and, yes, even went past the 30 per cent mark. But Calgary is seeing its vacancy rate go down, as 10 office buildings have been converted to residential properties. The math is simple: We have too much commercial space, and we’re in a housing crisis.

Wosnack said there are between six and eight office buildings in Edmonton that are ripe for residential conversion. This could add approximately 1,500 residential units to the core.

“You can deal with residential need, and create diversified housing, quickly,” he said. “It’s also an adaptive reuse strategy. It’s really important to use existing forms and change them from a use that doesn’t compete anymore. Many office buildings are becoming functionally obsolete. We need more residential. We need affordable residential. We need it quickly.”

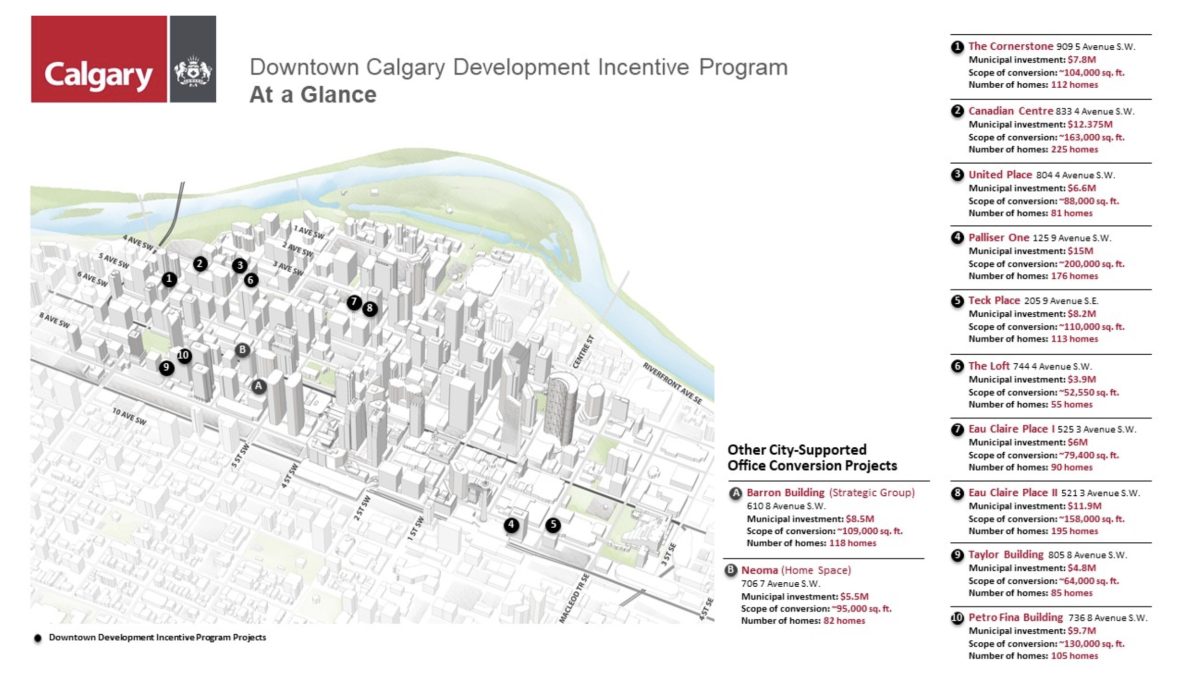

But conversions aren’t cheap, and they carry significant risks for investors. Interest rates are high, and construction costs have soared. So, Calgary created a Downtown Development Incentive Program; it offers $75 per square foot to a a developer who successfully completes an office-to-residential conversion. It also offers incentives for office towers that are converted into educational uses. The City of Calgary contributed approximately $87 million to those office conversions. The return is that Calgary boosts the number of downtown residents, and there are living, breathing taxpayers in buildings that were empty.

Thanks to the 10 conversion projects, Calgary’s commercial vacancy rate has dipped from 29.3 per cent to 27.3 per cent. It’s still a huge number, but it is trending in the right direction. It also shows just how much work many cities have to do to when it comes to addressing their gluts of commercial spaces.

Wosnack said that, while there is a lot of outside interest in Alberta right now, the institutional investment — the money that comes from group funds and pension plans — is “laser focused on Calgary.” In order to change that narrative, he said Edmonton has to continue changing the way that we all see downtown. And he would like to see Edmonton incentivize office conversions the way Calgary has. (Of course, we have to note his bias.)

The City’s Urban Planning Committee will be looking at the issue of office-to-residential conversions on Oct. 31. So far, there’s been no commitment from council on a program that’s similar to Calgary’s.

At an Urban Development Institute luncheon this week, Downtown Recovery Coalition Chair Alex Hryciw said it was vital for the City to have a strategy to convert offices that will never be offices again.

She said it’s hard for Edmonton to sell its residents on the idea of a 15-minute city, when that doesn’t even apply to the core. “We need more residents downtown,” she said.

Wosnack believes the repurposing of old office space to residential is a big part of how cities have to reimagine their downtowns. We have to change the perception of downtown as a place where people work from nine to five. It has to be seen as a place where people gather, play and learn.

And this all didn’t suddenly come about because of COVID. Wosnack said that Avison Young was already noting lower traffic in downtown buildings on Mondays and Fridays before the pandemic. We were already talking about working at home and shorter work weeks. COVID just accelerated the trend.

“If you’re still stuck on that outdated description, you’re focusing on the wrong goals,” said Wosnack. “It needs to be a central social district strategy.”

Yes, there are some significant wins — for example, the Rohit Group is taking over old office space on the west end of Jasper Avenue that was once home to Stantec. But, for the most part, the shortened work week is here to stay. Remote working won’t go away. And the City and the province are going to be cutting staff, not adding staff, in the years to come.

So, the focus has to be on making the core a place where more people are living — and learning.

A couple of weeks ago, I was invited to a “Field Trip,” organized by the Edmonton chapter of the Urban Development Institute. The purpose of the tour was to show us how our major educational institutions are contributing to city-building. And the excitement on the campuses of NorQuest College and MacEwan University was palpable; they are both bullish about their major expansion plans. MacEwan plans to have 20,000 full-time equivalent students downtown by 2030. NorQuest’s Campus Master Plan predicts that the number of students will rise from 8,141 full-time equivalents to 12,453 by 2030, then 16,000 by 2050.

Add to that the extra staff needed to look after those students, and the numbers are promising for downtown.

“If you took all the students who go to MacEwan and NorQuest right now, you could fill half of all the office buildings in downtown Edmonton,” said Wosnack. “We talk about how important it is to attract some big, new tech company to Edmonton, or see growth in our private sector, you are talking about hundreds of people. ‘Wouldn’t it be nice to have a 500-person company move to Edmonton?’ But we have 30,000 students who go to school in downtown Edmonton that nobody talks about. There’s a really great opportunity in front of us.”

(Article was edited Oct. 21)

Savvy AF. Blunt AF. Edmonton AF.